There are calls from the glass sector to rethink and even delay the soon to be introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR).

EPR will shift the financial responsibility for packaging waste from taxpayers to producers. Under the EPR scheme, businesses must collect and report detailed data on their packaging usage, which is then used to calculate household waste management fees.

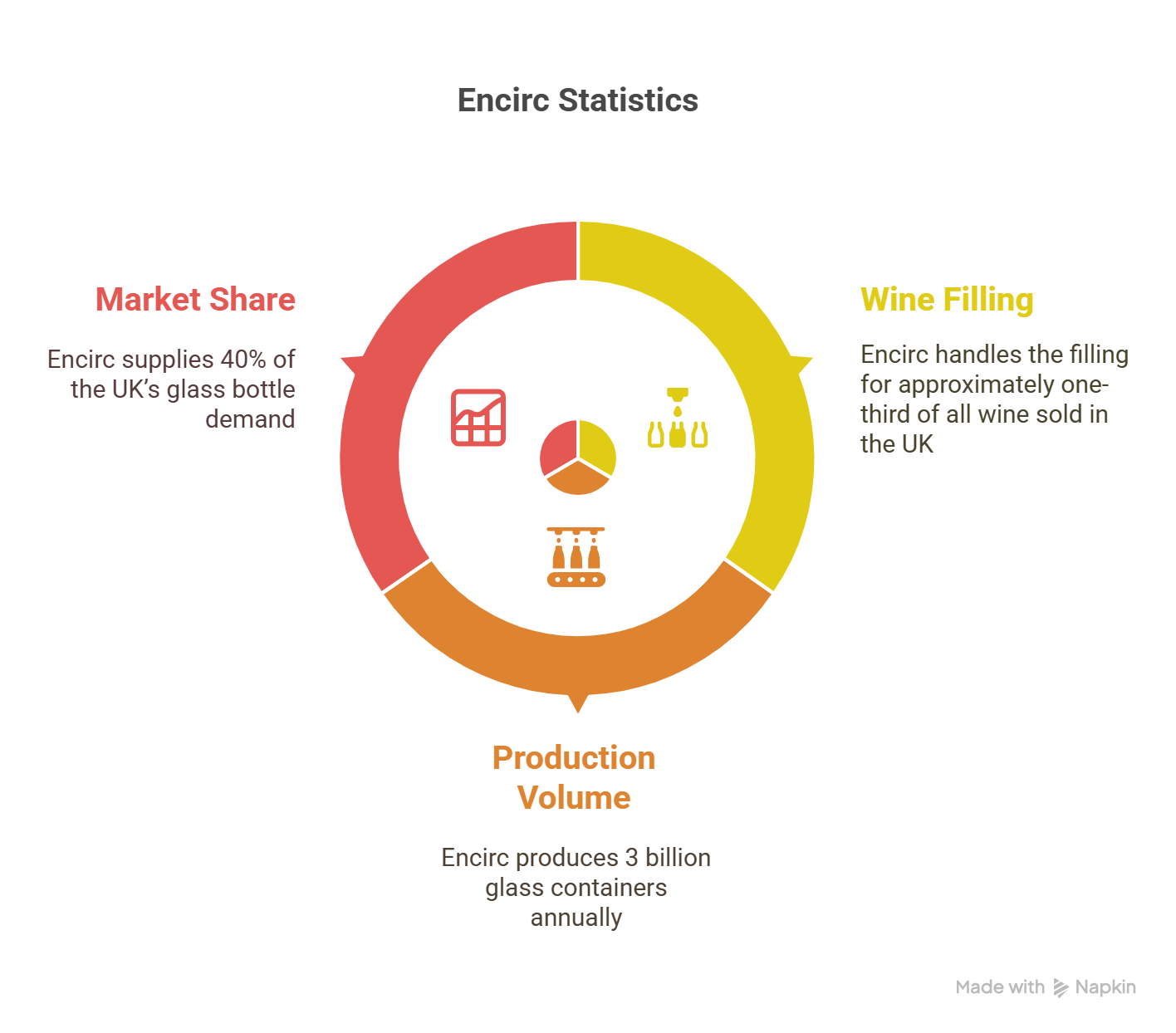

In theory, the more sustainable the packaging material, the lower the cost for producers. However, unlike in other countries around the world, the EPR scheme in the UK has been primarily formulated around weight rather than sustainability criteria, meaning that it will be particularly punitive for companies that use glass in the packaging supply chain.

Here, The Manufacturer speaks to Oliver Harry, Head of Corporate Affairs at glass manufacturer Encirc (part of Vidrala Group and current Manufacturer of the Year), to find out more and what needs to change to level the playing field.

Key takeaways

- UK’s EPR scheme penalises glass unfairly due to weight-based metrics

- Glass has strong environmental and health credentials

- The last vice of glass ‘carbon’ is being addressed and Encirc will be able to produce zero carbon glass bottles from the 2030s

- Current EPR setup could force brands to switch from glass to plastics

- There are calls for government rethink and delay EPR

FAQs

- What makes glass such a sustainable and recyclable material

- What is EPR and why it has been introduced?

- What will be the impact of EPR on food and bev manufacturers?

- Why it will be so punitive for glass manufacturers like Encirc?

- Why has EPR been set up in this way?

- What are Encirc doing to mitigate the impact?

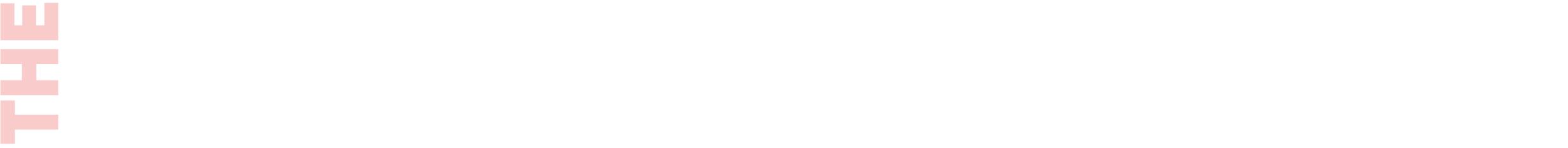

Encirc’s operations in the UK span three sites where it manufactures around three billion glass containers each year, serving more than a third of the glass bottle market and filling around a third of all wine in the country.

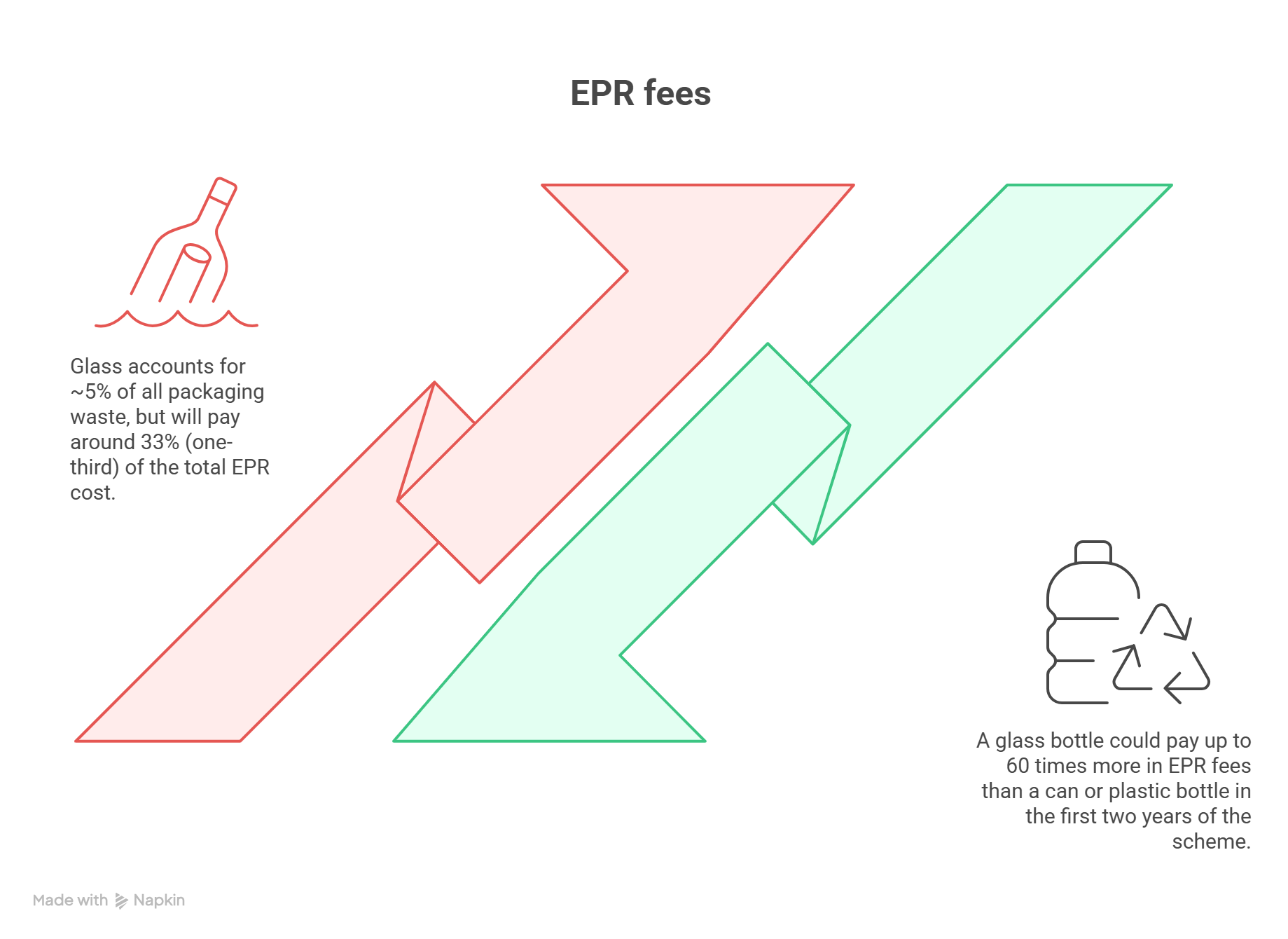

In terms of sustainability credentials, glass wins against competitive materials across every metric, with the exception of carbon. Environmentally, glass is the perfect material for the circular economy as it’s highly recyclable; in the UK a lot of glass is currently remelted back into bottles and is incorporated back into the supply chain.

Glass is also chemically inert which means that, unlike plastic, chemicals will not leach into food and drink products. Plastic packaging (and cans to an extent), involve thousands of chemicals – some of them carcinogenic. Indeed, citing a range of independent reports, Oliver is predicting that this issue in the supply chain could become a key health driver moving forward.

“Our sustainability director at Encirc has always claimed that plastics will be the next cigarettes,” he said. “Glass is the only material that’s chemically inert and locks its form into a stable format. Therefore, unlike plastic bottles, where thousands of chemicals will leach into your food or drink, that simply will not happen with glass. Even when you think of the aluminium cans we drink from. Each one has an internal plastic bag. So from a health perspective glass is very important.”

Let’s talk about carbon

However, glass is regularly attacked for having a higher carbon intensity when compared to plastic bottles or a cans. On face value, this would appear to be justified. Oliver explained that Encirc’s furnaces heat up to around 1,600°C degrees to melt down glass, utilising fossil fuels and gas to do so. In addition, glass is also heavier than plastic and so the cost of transporting glass packaging can increase the carbon intensity of the material.

However, this is something the glass industry is fully aware of and as such, is on a focused mission to solve this issue, as Oliver continued: “There won’t be a carbon problem within glass in ten years’ time. All glass manufacturers globally are going to solve their Scope 1 emissions, i.e., the furnaces they use for glass manufacture.”

Although a small amount of electricity has been used, the glass furnaces have traditionally been gas fueled. However, sustainable fuels are now starting to take over. Highly electrified on renewable electricity, glass furnaces are beginning to reap the benefits of hydrogen and bio fuels.

At its Cheshire plant, Encirc will be using energy from a local hydrogen production plant that will be operational by the end of the decade, providing very high levels of green electricity. In Northern Ireland, the company is also exploring biomethane, created from animal slurry from farms amongst other waste products.

“Deploying these sorts of methods will reduce our carbon intensity by 80%,” continued Oliver. “And by incorporating extra carbon capture, which is also part of our plans, we think we’ll be able to produce zero carbon glass bottles from the 2030s onwards; thus solving the carbon issue – essentially the last vice of glass.”

Why has the EPR initiative been introduced?

The EPR has been on its way for some time and similar schemes have been rolled out successfully in other locations around the world. It’s therefore an idea that Encirc is behind in principle, as it takes the costs of collecting and recycling waste away from the local authority or the taxpayer and places that burden on the producer that is manufacturing the goods.

The key to the scheme lies in the fact that the worse an item of packaging is for the environment, the more the producer has to pay. If it’s complex and hard to recycle, for example, the onus is on the manufacturer to use better materials, which in turn will then reduce the cost of production and create a more responsible packaging system.

When analysing EPR schemes in other countries, Oliver said that cost comparisons for glass against cans and plastics were favourable and as such, the company weren’t particularly apprehensive about the introduction of EPR in the UK. However, as Oliver continued, the focus on the metric of weight means that the scheme has been set up very differently in the UK and in this guise, will be particularly punitive for glass manufacturers.

“The metric that the EPR has employed in the UK is critical for glass, so much so that it’s more than double the cost of any other EPR scheme on the planet. Primarily, this is because the UK EPR has been established on a weight-based system, rather than focusing on the environmental credentials of the materials.

“The UK’s system is completely skewed, and glass will end up paying many times more than its competitor (and often much less recyclable) materials.”

Feeling the impact

Compounding the issue is the fact that the UK is set to introduce a deposit return scheme (DRS) from late 2027. Under the scheme, consumers will be able to place certain types of packaging waste into reverse vending machines, and claim money back.

As part of the DRS, plastic bottles and cans avoid being included in the EPR. Not only that, but the economics of a DRS when applied to glass simply don’t add up in the same way as it does for other materials (glass is heavier and can’t be flatten down for recycling etc) and as such, glass has been excluded from the DRS altogether. This means that not only is glass paying a disproportionate amount into the EPR (around a third of the cost despite only accounting for five per cent of all waste in the UK), plastic bottles and cans avoid the EPR costs entirely.

“The result is that for the first two years of this scheme, a glass bottle will pay anything up to 60 times more than a can or a plastic bottle for end of life costs, despite the fact that it’s an infinitely more recyclable material, and that’s a real issue,” added Oliver.

Encirc has gathered very clear evidence from customer surveys that consumers prefer drinking beer, wine and soft drinks from glass, due to its chemically inert nature. However, Oliver fears that global drinks brands will have no choice but to move away from heavy materials like glass, to lighter alternatives such as cans and plastics in order to save costs after the EPR is introduced.

“We’re already seeing evidence of this happening with many products,” Oliver continued. “What the government will argue is that the higher fees for glass use will promote reuse, which in turn will avoid EPR costs.

“Our response, however, is while we see opportunities in reuse – we think glass can actually form the centre of a reuse economy – this won’t create an immediate reuse revolution. Sadly, it will just spur brands to move very quickly away from glass and towards more environmentally unfriendly alternatives in order to save costs.

“A reuse system can take a decade to set up, and once products move away from glass, and furnaces start closing down, those glass products won’t come back. So there is the worry that we’ll lose that manufacturing industry from the UK. We knew the EPR scheme was coming; what we didn’t envisage was the extraordinarily high costs that Defra and the government have placed on glass.”

“We have a good doorstep collection scheme in the UK so our view for heavy materials like glass, is that we should utilise our existing recycling infrastructure.”

Why is glass being hit so hard?

Oliver added that there are few at Encirc who fully understand the decision the government has taken. “The argument coming from government is that the EPR fees are based on what it costs to process glass through the system. However, these figures are heavily refuted by the industry.”

Encirc are lobbying the government to take a step back, rethink EPR and ideally delay its introduction. Not least because its impact, Oliver claims, is also going to be felt strongly by the hospitality sector which is already feeling the strain from other challenges.

He continued: “We’re not asking for EPR to be cancelled as a policy because broadly, we’re in favour. But we feel it needs to be brought in line with other schemes around the world, where a very sensible approach has been taken to EPR and an effort has been made to try to reach material parity in terms of cost – so one material doesn’t have a competitive advantage over another.”

The UK’s approach to EPR has failed to incorporate best practice from elsewhere in the world, and while Oliver believes the high fees for glass are partly due to the desire of the government to push the material into reuse as fast as possible, it’s a stick rather than carrot approach. And rather than promote reuse, Oliver believes the impact of the EPR will only lead to a rapid shift away from glass as people look to avoid the very high and immediate costs involved.

And the clock is ticking. Drinks brands will have to pay their annual EPR fees in October, yet, at the time of writing, they don’t know what those final fees are going to be. Understandably, companies are currently pulling their hair out when it comes to EPR. Confirmation of the final fees are expected by the end of June, so businesses won’t have long to prepare. As a consequence, many are just having to make predictions.

“It’s understandable that many drinks brands are unsure of what to do and are asking themselves how best to avoid these high fees. Despite the fact that consumers undoubtedly prefer glass, many are looking seriously at switching materials. Our message is to hold steady; we’re hoping the government will reach a sensible decision so we would urge businesses not to move away from the most sustainable material for a short-term reaction.

“Also, in the medium-term we will begin to see a pressure to shift away from packaging that leaches dangerous chemicals into food and drink. In my view glass will then be seen as the perfect packaging for the health of consumers, which will be a real boost to our industry. But we need to keep our industry in the meantime!”

How is Encirc planning to mitigate the impact of EPR?

As a Vidrala business Encirc is lobbying, talking to ministers, writing letters, and pushing as hard as possible for a rethink on the EPR initiative. The company is also working closely with customers to ensure wherever possible that they stay with glass.

The environmental impact of single use plastics are well-known but even for recyclable plastics, there are long-term health impacts, as every time a plastic bottle is recycled it increases the amount of chemicals in the bottle. Additionally, Encirc is lowering the carbon intensity of glass to the point where the company believe it will be manufacturing zero carbon glass bottles by the end of the 2030s.

“And it’s not just us that are calling for a more pragmatic and sensible approach in line with other countries around the world. All the trade associations are saying the same thing, including the Scotch Whisky Association, British Glass and the Wine and Spirits Trade Association (WSTA), as well as many major consumer and household brands.”

What are the key milestones to be mindful of?

With the final EPR fees expected by the end of the month, food and drinks brands will be expected to pay fees from October. A year later, an element of the initiative called modulation will come into force whereby environmental criteria, which will have the potential to reduce or increase the price of EPR, will be added to certain products.

The first of these will be based on recyclability, which Oliver hopes will reflect well on glass. The modulation will be based around a traffic light style system, of green, amber and red, whereby the red materials i.e., those that have poorer recyclable credentials, will pay and offset the cost of greener products. Modulation should therefore reduce the price of the products in the EPR that are doing well in terms of recyclability.

Every year thereafter, another set of criteria will be released which will analyse products under that particular microscope to increase or reduce EPR fees. “The issue for us is the immediate milestones which focus on the EPR price for glass which has been worked out using the wrong metric. That needs to be addressed urgently, if not, the whole scheme needs to be put back, and rethought,” added Oliver.

Not only that but Oliver also highlighted a separate concern around EPR in that, as the scheme has been established to pay for the recycling cost of products, the assumption is that this funding would be ring-fenced. However, it’s merely being paid as a sum of money to local authorities.

The worry therefore, is that EPR won’t actually go towards improving the recycling infrastructure of the UK, but rather, fees will be poured into generic pot to fund the myriad of other challenges facing local authorities. This endangers the intention of the EPR to improve products that go to market, make them more recyclable and more environmentally friendly, and to improve recycling infrastructure. Oliver concluded: “Glass is going to be the sustainable material of choice. We just hope common sense prevails with the government on EPR, to protect both our industry and in my view, the most important sustainable packaging material.”

For more articles like this, visit our Sustainability channel